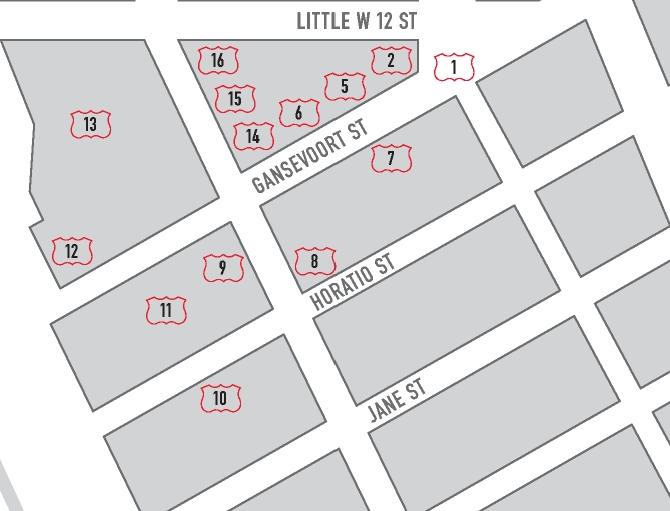

The area you will be walking through is not large, bounded by Horatio Street (and Greenwich Village) on the south, 16th Street (and Chelsea) on the north, Hudson Street and Ninth Avenue on the east, and West Street. Yet Gansevoort Market is one of Manhattan's defining neighborhoods - gritty, hard working, low-rise, with its own special character, and a rich collection of buildings and history that cannot be replaced.

BACKGROUND

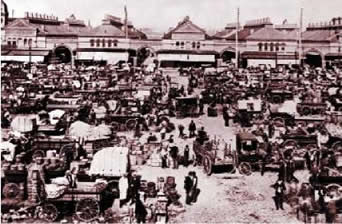

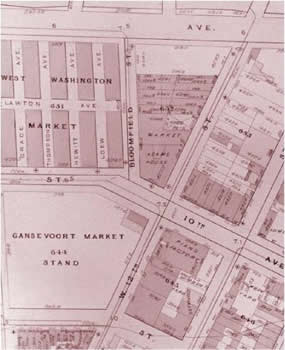

Today's Gansevoort Market area is actually the site of three distinct markets that have existed here at various times during the past century and a half. the original Gansevoort Farmer's Market, the West Washington Market, and today's Gansevoort Market Meat Center.

The original Gansevoort Market took its name from its location on Gansevoort Street. Originally an Indian trail leading to the Hudson River, later called the Great Kill or Old Kill Road, the street was renamed in 1837 for Fort Gansevoort, which had been hastily built in anticipation of the War of 1812 with Great Britain. The fort in turn had been named for General Peter Gansevoort, who had fought in the American Revolution. By a twist of literary fate, Gansevoort's grandson, the novelist Herman Melville, spent the years from 1866 to 1885 working as a Customs inspector for the Department of Docks in a long-since vanished building on the wharf at the foot of the street named for his grandfather.

THE HISTORY OF THE MARKETS

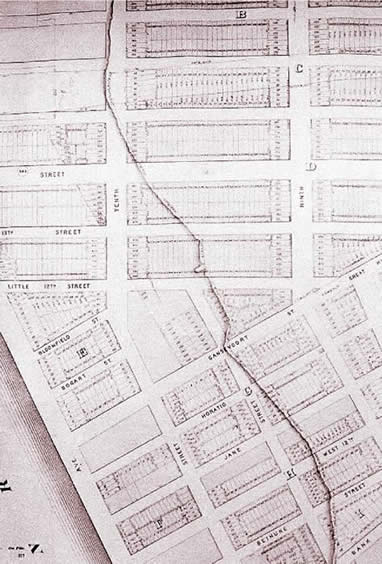

New York City began planning a market on Gansevoort Street more than fifty years before the market's actual opening in 1884. As early as 1831, worried that the older markets to the south were becoming unmanageably overcrowded, the City proposed acquiring underwater property near Gansevoort Street, owned by the Astor family, in order to create landfill for a new market district. The sale was finally completed in 1851, at which time the shoreline was filled in.

In 1854 the City again announced plans for a market, but nothing much happened. That same year, a freight depot for the Hudson River Railroad opened on Gansevoort Street and West Street, and by the mid-186os a number of vendors had left the downtown Washington Market and set up business by the depot. By 188o, the City declared that the block bounded today by Gansevoort, Little West 12th, Washington and West streets, plus blocks to the west on landfill, would become a public market. The Gansevoort Market officially opened in 1884 on the enormous paved open-air block between Gansevoort and Little West 12th streets, on the site of the former Fort Gansevoort, and of the future Gansevoort Meat Center.